Tuesday, December 9

Indo-Pakistani Crisis

We begin with an Indian strike on Pakistan, precipitating a withdrawal of Pakistani troops from the Afghan border, resulting in intensified Taliban activity along the border and a deterioration in the U.S. position in Afghanistan, all culminating in an emboldened Iran. The scenario is not unlikely, assuming India chooses to strike.

Our argument that India is likely to strike focused, among other points, on the weakness of the current Indian government and how it is likely to fall under pressure from the opposition and the public if it does not act decisively. An unnamed Turkish diplomat involved in trying to mediate the dispute has argued that saving a government is not a good reason to go to war. That is a good argument, except that in this case, not saving the government is unlikely to prevent a war, either.

If India’s Congress party government were to fall, its replacement would be even more likely to strike at Pakistan. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), Congress’ Hindu nationalist rival, has long charged that Congress is insufficiently aggressive in combating terrorism. The BJP will argue that the Mumbai attack in part resulted from this failing. Therefore, if the Congress government does not strike, and is subsequently forced out or loses India’s upcoming elections, the new government is even more likely to strike.

It is therefore difficult to see a path that avoids Indian retaliation, and thus the emergence of at least a variation on the scenario we laid out. But the problem is not simply political: India must also do something to prevent more Mumbais. This is an issue of Indian national security, and the pressure on India’s government to do something comes from several directions.

Three Indian Views of Pakistan

The question is what an Indian strike against Pakistan, beyond placating domestic public opinion, would achieve. There are three views on this in India.

The first view holds that Pakistani officials aid and abet terrorism — in particular the Pakistani Inter-Service Intelligence (ISI), which serves as Pakistan’s main intelligence service. In this view, the terrorist attacks are the work of Pakistani government officials — perhaps not all of the government, but enough officials of sufficient power that the rest of the government cannot block them, and therefore the entire Pakistani government can be held accountable.

The second view holds that terrorist attacks are being carried out by Kashmiri groups that have long been fostered by the ISI but have grown increasingly autonomous since 2002 — and that the Pakistani government has deliberately failed to suppress anti-Indian operations by these groups. In this view, the ISI and related groups are either aware of these activities or willfully ignorant of them, even if ISI is not in direct control. Under this thinking, the ISI and the Pakistanis are responsible by omission, if not by commission.

The third view holds that the Pakistani government is so fragmented and weak that it has essentially lost control of Pakistan to the extent that it cannot suppress these anti-Indian groups. This view says that the army has lost control of the situation to the point where many from within the military-intelligence establishment are running rogue operations, and groups in various parts of the country simply do what they want. If this argument is pushed to its logical conclusion, Pakistan should be regarded as a state on the verge of failure, and an attack by India might precipitate further weakening, freeing radical Islamist groups from what little control there is.

The first two analyses are essentially the same. They posit that Pakistan could stop attacks on India, but chooses not to. The third is the tricky one. It rests on the premise that the Pakistani government (and in this we include the Pakistani army) is placing some restraint on the attackers. Thus, the government’s collapse would make enough difference that India should restrain itself, especially as any Indian attack would so destabilize Pakistan that it would unleash our scenario and worse. In this view, Pakistan’s civilian government has only as much power in these matters as the army is willing to allow.

The argument against attacking Pakistan therefore rests on a very thin layer of analysis. It requires the belief that Pakistan is not responsible for the attacks, that it is nonetheless restraining radical Islamists to some degree, and that an Indian attack would cause even these modest restraints to disappear. Further, it assumes that these restraints, while modest, are substantial enough to make a difference.

There is a debate in India, and in Washington, as to whether this is the case. This is why New Delhi has demanded that Pakistan turn over 20 individuals wanted by India in connection with attacks. The list doesn’t merely include Islamists, but also Lt. Gen. Hamid Gul, the former head of the ISI who has long been suspected of close ties with Islamists. (The United States apparently added Gul to the list.) Turning those individuals over would be enormously difficult politically for Pakistan. It would create a direct confrontation between Pakistan’s government and the Pakistani Islamist movement, likely sparking violence in Pakistan. Indeed, turning any Pakistani over to India, regardless of ideology, would create a massive crisis in Pakistan.

The Indian government chose to make this demand precisely because complying with it is enormously difficult for Pakistan. New Delhi is not so much demanding the 20 individuals, but rather that Pakistan take steps that will create conflict in Pakistan. If the Pakistani government is in control of the country, it should be able to weather the storm. If it can’t weather the storm, then the government is not in control of Pakistan. And if it could weather the storm but chooses not to incur the costs, then India can reasonably claim that Pakistan is prepared to export terrorism rather than endure it at home. In either event, the demand reveals things about the Pakistani reality.

The View from Islamabad

Pakistan’s evaluation, of course, is different. Islamabad does not regard itself as failed because it cannot control all radical Islamists or the Taliban. The official explanation is that the Pakistanis are doing the best they can. From the Pakistani point of view, while the Islamists ultimately might represent a threat, the threat to Pakistan and its government that would arise from a direct assault on the Islamists is a great danger not only to Pakistan, but also to the region. It is thus better for all to let the matter rest. The Islamist issue aside, Pakistan sees itself as continuing to govern the country effectively, albeit with substantial social and economic problems (as one might expect). The costs of confronting the Islamists, relative to the benefits, are therefore high.

The Pakistanis see themselves as having several effective counters against an Indian attack. The most important of these is the United States. The very first thing Islamabad said after the Mumbai attack was that a buildup of Indian forces along the Pakistani border would force Pakistan to withdraw 100,000 troops from its Afghan border. Events over the weekend, such as the attack on a NATO convoy, showed the vulnerability of NATO’s supply line across Pakistan to Afghanistan.

The Americans are fighting a difficult holding action against the Taliban in Afghanistan. The United States needs the militant base camps in Pakistan and the militants’ lines of supply cut off, but the Americans lack the force to do this themselves. A withdrawal of Pakistani forces from the Afghan border would pose a direct threat to American forces. Therefore, the Pakistanis expect Washington to intervene on their behalf to prevent an Indian attack. They do not believe a major Indian troop buildup will take place, and if it does, the Pakistanis do not think it will lead to substantial conflict.

There has been some talk of an Indian naval blockade against Pakistan, blocking the approaches to Pakistan’s main port of Karachi. This is an attractive strategy for India, as it plays to New Delhi’s relative naval strength. Again, the Pakistanis do not believe the Indians will do this, given that it would cut off the flow of supplies to American troops in Afghanistan. (Karachi is the main port serving U.S. forces in Afghanistan.) The line of supply in Afghanistan runs through Pakistan, and the Americans, the Pakistanis calculate, do not want anything to threaten that.

From the Pakistani point of view, the only potential military action India could take that would not meet U.S. opposition would be airstrikes. There has been talk that the Indians might launch airstrikes against Islamist training camps and bases in Pakistani-administered Kashmir. In Pakistan’s view, this is not a serious problem. Mounting airstrikes against training camps is harder than it might seem. The only way to achieve anything in such a facility is with area destruction weapons — for instance, using B-52s to drop ordnance over very large areas. The targets are not amenable to strike aircraft, because the payload of such aircraft is too small. It would be tough for the Indians, who don’t have strategic bombers, to hit very much. Numerous camps exist, and the Islamists can afford to lose some. As an attack, it would be more symbolic than effective.

Moreover, if the Indians did kill large numbers of radical Islamists, this would hardly pose a problem to the Pakistani government. It might even solve some of Islamabad’s problems, depending on which analysis you accept. Airstrikes would generate massive support among Pakistanis for their government so long as Islamabad remained defiant of India. Pakistan thus might even welcome Indian airstrikes against Islamist training camps.

Islamabad also views the crisis with India with an eye to the Pakistani nuclear arsenal. Any attack by India that might destabilize the Pakistani government opens at least the possibility of a Pakistani nuclear strike or, in the event of state disintegration, of Pakistani nuclear weapons falling into the hands of factional elements. If India presses too hard, New Delhi faces the unknown of Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal — unless, of course, the Indians are preparing a pre-emptive nuclear attack on Pakistan, something the Pakistanis find unlikely.

All of this, of course, depends upon two unknowns. First, what is the current status of Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal? Is it sufficiently reliable for Pakistan to count on? Second, to what extent do the Americans monitor Pakistan’s nuclear capabilities? Ever since the crisis of 2002, when American fears that Pakistani nuclear weapons could fall into al Qaeda’s hands were high, we have assumed that American calm about Pakistan’s nuclear facilities was based on Washington’s having achieved a level of transparency on their status. This might limit Pakistan’s freedom of action with regard to — and hence ability to rely on — its nuclear arsenal.

Notably, much of Pakistan’s analysis of the situation rests on a core assumption — namely, that the United States will choose to limit Indian options, and just as important, that the Indians would listen to Washington. India does not have the same relationship or dependence on the United States as, for example, Israel does. India historically was allied with the Soviet Union; New Delhi moved into a strategic relationship with the United States only in recent years. There is a commonality of interest between India and the United States, but not a dependency. India would not necessarily be blocked from action simply because the Americans didn’t want it to act.

As for the Americans, Pakistan’s assumption that the United States would want to limit India is unclear. Islamabad’s threat to shift 100,000 troops from the Afghan border will not easily be carried out. Pakistan’s logistical capabilities are limited. Moreover, the American objection to Pakistan’s position is that the vast majority of these troops are not engaged in controlling the border anyway, but are actually carefully staying out of the battle. Given that the Americans feel that the Pakistanis are ineffective in controlling the Afghan-Pakistani border, the shift from virtually to utterly ineffective might not constitute a serious deterioration from the United States’ point of view. Indeed, it might open the door for more aggressive operations on — and over — the Afghan-Pakistani border by American forces, perhaps by troops rapidly transferred from Iraq.

The situation of the port of Karachi is more serious, both in the ground and naval scenarios. The United States needs Karachi; it is not in a position to seize the port and the road system out of Karachi. That is a new war the United States can’t fight. At the same time, the United States has been shifting some of its logistical dependency from Pakistan to Central Asia. But this requires a degree of Russian support, which would cost Washington dearly and take time to activate. In short, India’s closing the port of Karachi by blockade, or Pakistan’s doing so as retaliation for Indian action, would hurt the United States badly.

Supply lines aside, Islamabad should not assume that the United States is eager to ensure that the Pakistani state survives. Pakistan also should not assume that the United States is impressed by the absence or presence of Pakistani troops on the Afghan border. Washington has developed severe doubts about Pakistan’s commitment and effectiveness in the Afghan-Pakistani border region, and therefore about Pakistan’s value as an ally.

Pakistan’s strongest card with the United States is the threat to block the port of Karachi. But here, too, there is a counter to Pakistan: If Pakistan closes Karachi to American shipping, either the Indian or American navy also could close it to Pakistani shipping. Karachi is Pakistan’s main export facility, and Pakistan is heavily dependent on it. If Karachi were blocked, particularly while Pakistan is undergoing a massive financial crisis, Pakistan would face disaster. Karachi is thus a double-edged sword. As long as Pakistan keeps it open to the Americans, India probably won’t block it. But should Pakistan ever close the port in response to U.S. action in the Afghan-Pakistani borderland, then Pakistan should not assume that the port will be available for its own use.

India’s Military Challenge

India faces difficulties in all of its military options. Attacks on training camps sound more effective than they are. Concentrating troops on the border is impressive only if India is prepared for a massive land war, and a naval blockade has multiple complications.

India needs a military option that demonstrates will and capability and decisively hurts the Pakistani government, all without drawing India into a nuclear exchange or costly ground war. And its response must rise above the symbolic.

We have no idea what India is thinking, but one obvious option is airstrikes directed not against training camps, but against key government installations in Islamabad. The Indian air force increasingly has been regarded as professional and capable by American pilots at Red Flag exercises in Nevada. India has modern Russian fighter jets and probably has the capability, with some losses, to penetrate deep into Pakistani territory.

India also has acquired radar and electronic warfare equipment from Israel and might have obtained some early precision-guided munitions from Russia and/or Israel. While this capability is nascent, untested and very limited, it is nonetheless likely to exist in some form.

The Indians might opt for a drawn-out diplomatic process under the theory that all military action is either ineffective or excessively risky. If it chooses the military route, New Delhi could opt for a buildup of ground troops and some limited artillery exchanges and tactical ground attacks. It also could choose airstrikes against training facilities. Each of these military options would achieve the goal of some substantial action, but none would threaten fundamental Pakistani interests. The naval blockade has complexities that could not be managed. That leaves, as a possible scenario, a significant escalation by India against targets in Pakistan’s capital.

The Indians have made it clear that the ISI is their enemy. The ISI has a building, and buildings can be destroyed, along with files and personnel. Such an aerial attack also would serve to shock the Pakistanis by representing a serious escalation. And Pakistan might find retaliation difficult, given the relative strength of its air force. India has few good choices for retaliation, and while this option is not a likely one, it is undoubtedly one that has to be considered.

It seems to us that India can avoid attacks on Pakistan only if Islamabad makes political concessions that it would find difficult to make. The cost to Pakistan of these concessions might well be greater than the benefit of avoiding conflict with India. All of India’s options are either ineffective or dangerous, but inactivity is politically and strategically the least satisfactory route for New Delhi. This circumstance is the most dangerous aspect of the current situation. In our opinion, the relative quiet at present should not be confused with the final outcome, unless Pakistan makes surprising.

Read more!

Sunday, December 7

Arctic Ocean – The New Cold War

Arctic Ocean – The Cold War for the Cold Region

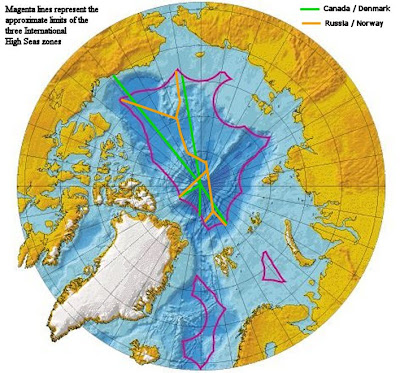

Canada, Russia, the US, Denmark [via Greenland] and Norway are staking claims in the Arctic Ocean, which may contain a quarter of the world's untapped petroleum reserves, and is becoming more accessible due to global warming. Under the Convention on the Law of the Sea, they could acquire rights to Arctic seafloor territory if the areas are linked to their continental shelves. Russia made its claim in 2001, though it will make a resubmission. Canada ratified the Law on the Sea in 2003, so it has to file its claim by 2013. The United States had not ratified the Law of the Sea Convention.

In recent decades, it has been well recognized that published portrayals of the sea floor north of the Arctic Circle, particularly in the deep central basin of the Arctic Ocean, are not totally accurate, and that in certain areas, there are significant discrepancies between observed and charted depths. The principal cause of this situation has been the lack of sounding information needed to construct reliable and detailed charts: certain regions remain inadequately mapped on account of difficult operating conditions, or because critical data sets have not been made available for widespread public use.

The severe climatic and ice conditions in the Arctic Ocean make it difficult to apply some of the existing methods and technologies that are generally easy to use in other oceans, in order to obtain the information that is necessary for establishing the outer limits of the Continental Shelf.

The floor of the Arctic Ocean is characterized by the existence of at least four large submarine elevations that could be considered to be submerged prolongations of the continental margins beyond 200 nautical miles: Chukchi Plateau, Mendeleyev Ridge, Lomonosov Ridge, and Alpha Ridge. Adequate sets of geological and geophysical data, together with bathymetric and morphological information, are seen as critical to establishing that such elevations are indeed natural components of the continental margin.

The U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, or UNCLOS, stipulates that any coastal state can claim territory 200 nautical miles from their shoreline and exploit the natural resources within that zone. Nations can also extend that limit to up to 350 nautical miles from their coast if they can provide scientific proof that the undersea continental plate is a natural extension of their territory.

Continental shelf claims beyond 200 nautical miles are made according to the provisions of Article 76 of the Law of the Sea. The implementation of Article 76 rests fundamentally upon the analysis and interpretation of bathymetric and geological information. A 1996 Workshop assembled specialists from the five coastal states that border the Arctic Ocean (Canada, Denmark, Norway, Russia, and the United States of America) to discuss scientific and technical issues relating to the preparation of continental shelf claims beyond 200 nautical miles. During the course of the 1996 Workshop, it was recognized that all five coastal states have valid grounds for developing continental shelf claims beyond their 200 nautical mile limits, and that the possibility, if not the likelihood, existed of overlapping claims between neighbouring states.

Article 76 of UNCLOS specifies a mechanism for extending the limits of the continental shelf beyond the 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ). After ratification of UNCLOS a country has ten years to collect the appropriate information and submit a claim for an extended continental shelf to the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS).

Much of the argument revolves around the underwater Lomonosov Ridge. Mikhail Vasil'evich Lomonosov was the first Russian natural scientist of world importance. His major scientific accomplishment was in the field of physical chemistry, with other notable discoveries in astronomy, geophysics, geology and mineralogy. He founded what became Moscow State University, in 1755. This university, officially named after Lomonosov, is at the apex of the Russian system of higher education.

The Lomonosov Ridge is an undersea chain of mountains rising some 2500 meters above the Arctic floor. Measuring about 1700 km in length, the Lomonosov Ridge is considered to be of continental origin, a sliver that was separated from the Kara and Barents shelves and transported to its present position by sea-floor spreading.

The General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO, Canadian Hydrographic Service, 1979) served as an authoritative portrayal of the seafloor north of 64°N. The International Bathymetric Chart of the Arctic Ocean (IBCAO) was developed from an accumulation of bathymetric measurements collected during past and modern expeditions. Striking discrepancies between the GEBCO and IBCAO portrayals of the Lomonosov Ridge occur between the North Pole and the Siberian continental shelf. The new model shows a far more complex morphology, with a ridge that is broken into several smaller segments.

Countries have the possibility of claiming the Lomonosov Ridge, a submarine mountain range, as a natural prolongation of their land territory. Bathymetry, seismic and gravity data are needed to substantiate the claim. Out to a distance of 350 nautical miles or further, if coastal states can claim the Lomonosov Ridge as a natural prolongation of land territory, coastal states can exercise specified sovereign rights. These rights include the right to explore and exploit mineral and biological resources on and below the seabed and jurisdiction in matters related to environment and conservation.

The Lomonosov Ridge, which Russia claims is part of their continental shelf, is clearly a separate oceanic seafloor volcanic ridge and thus not part of Russia's continental shelf. The Russian UNCLOS claim over the Arctic Commons Abyssal area adjacent to the edge of their continental shelf was rejected in 2001 by the Commission for the Continental Shelf, as the geological facts proved that the claim had no basis under UNCLOS rules. The geology of the area in question has not changed since the Russian claim was rejected.

Russia's Oceanology research institute has undertaken two Arctic expeditions - to the Mendeleyev underwater chain in 2005 and to the Lomonosov ridge in August 2007 - on orders from the ministry to back Russian claims to the region, believed to contain vast oil and gas reserves and other mineral riches, likely to become accessible in future decades due to man-made global warming. The Natural Resources Ministry said in September 2007 that preliminary results of research carried out by Russian scientists will allow the country to claim 1.2 million sq km (460,000 sq miles) of potentially energy-rich Arctic territory. On 04 October 2007 Russia's natural resources minister said the development of the Lomonosov underwater mountain chain in the Arctic could bring Russia up to 5 billion metric tons of equivalent fuel. "Reaching the Lomonosov ridge means for Russia potentially up to 5 billion tons of equivalent fuel," Yury Trutnev said

In August 2008 Canadian researchers teamed with Danish scientists to offer proof that the Lomonosov Ridge is a natural extension of the North American continent. Their landmark findings, the initial result of years of sea floor mapping and millions of dollars in research investments by the Canadian and Danish governments, were presented at the 2008 International Geological Congress in Oslo under the innocuous title "Crustal Structure from the Lincoln Sea to the Lomonosov Ridge, Arctic Ocean."

Denmark hopes to collect evidence that will support a claim that the continental shelf of Greenland-a province of Denmark-extends to the North Pole. Norway is the only other country (besides Russia) that has filed a legal claim to extend its continental shelf into a portion of the Arctic Ocean.

Arctic sea ice during the 2007 melt season plummeted to the lowest levels since satellite measurements began in 1979. The average sea ice extent for the month of September was 4.28 million square kilometers (1.65 million square miles), the lowest September on record, shattering the previous record for the month, set in 2005, by 23 percent.

Arctic sea ice receded so much that the fabled Northwest Passage completely opened for the first time in human memory during 2007. Explorers and other seafarers had long recognized that this passage, through the straits of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, represented a potential shortcut from the Pacific to the Atlantic. Roald Amundsen began the first successful navigation of the route starting in 1903. It took his group two-and-a-half years to leapfrog through narrow passages of open water, with their ship locked in the frozen ice through two cold, dark winters. More recently, icebreakers and ice-strengthened ships have on occasion traversed the normally ice-choked route. However, by the end of the 2007 melt season, a standard ocean-going vessel could have sailed smoothly through. On the other hand, the Northern Sea Route, a shortcut along the Eurasian coast that is often at least partially open, was completely blocked by a band of ice in 2007.

In 2007 National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) Senior Scientist Mark Serreze said, “The sea ice cover is in a downward spiral and may have passed the point of no return. As the years go by, we are losing more and more ice in summer, and growing back less and less ice in winter. We may well see an ice-free Arctic Ocean in summer within our lifetimes.” The scientists agree that this could occur by 2030.

Discovery of oil fields and natural gas in the artic has led to an increased interest in the development of ice-breaking cargo vessels and/or tankers for use in transporting these resources to refineries and consumers at remotely situated markets. The cargo and/or tanker ships must operate efficiently during the transportation of their cargo. In order to operate efficiently, they must maintain a satisfactory speed with a relatively low fuel consumption. In order to meet these efficiency requirements, conventional ship designs have been developed. Such conventional designs have a low value of ship-ice resistance per unit cargo capacity. Such conventional designs are generally characterized by a relatively large length-to-beam ratio, fine bow forms and long parallel middle-body sections. Such hull designs allow the ship to perform efficiently during normal travel through non-ice-covered waters, and to perform well during straight travel through ice-covered waters. However, due to their relatively long parallel middle body sections, these conventional ships have poor maneuverability in ice-covered waters. The poor maneuverability of the conventional design has presented serious problems when attempting to turn these ships in order to change course in ice-covered waters to avoid objects, such as a major ice ridge or for maneuvering the ship into a docking facility. Accordingly, the poor maneuverability of such conventional designs within ice-covered waters deterimentally affects the safe operation and time required to effectively dock and position the vessel.

The progress of a conventional vessel through ice is dependent mainly on the thickness and type of ice; the thrust of the propeller or propellers; the shape of the hull, with particular emphasis on the forward section; and friction between the hull of the vessel and the ice. Should any of the above factors change or be changed then the vessel's performance would change. The ability of a vessel to steer, when operating in ice, is dependent principally on the thickness and characteristics of the ice; the shape of the bow section; the shape of the stern section; the thrust of the propeller and size of the rudder; and possibly of greatest influence, the length of parallel body (straight ship sides). So, although most vessels, other than ice breakers, have trouble in navigating in ice covered waterways, some have a lot more trouble than others, and this difficulty is proportionately increased with ship length.

In order to avoid safety hazards and attempt to minimize the transit time required to specifically maneuver the vessel, some ships have been designed to serve as the primary ice-breaking vessels. Such vessels escort the conventional cargo ships, clearing the path in front of the cargo ship. Such ice-breaking ships must have both a high maneuverability in the ice and cut a wide channel for the cargo vessel in which to follow. The necessary maneuverability, and ability to form a wide channel are made possible by providing such ice-breaking vessels with a stocky, rounded hull with a relatively low length-to-beam ratio, typically in the range of 4.0 to 5.5. The water plane-shape of this type of hull enables a certain degree of turning within the confines of the channel cut by the ship's beam. However, such a high beam-to-displacement ratio makes such a vessel configuration unsuitable as a cargo vessel. The high beam-to-displacement ratio results in a relatively high power requirement per unit cargo capacity which is moved. Furthermore, this high beam-to-displacement ratio results in an increased open water resistance per unit displacement. Therefore, such vessels do not travel efficiently through ice-covered or non-ice-covered waters.

Another design which has been developed in order to increase the maneuverability of a cargo ship in ice-covered waters includes a wide beam forward configuration. The object of the wide beam forward design is to cause the ship's bow to cut a sufficiently wide channel through the ice to allow a relatively narrow middle body and stern to swing outward to either side during a turning maneuver. This concept was embodied in a converted tanker SS Manhattan. While the wide beam forward design does provide a certain degree of improved turning capability in ice-covered waters, it suffers to some extent from the same effects as the stocky, rounded hull escort vessel discussed above. The wide beam forward configuration requires greater propulsion power per unit displacement in order to break through the ice than is required by an equivalent sized ship having a relatively high length-to-beam ratio. Therefore, although the wide beam forward configuration allows for greater maneuverability during turns in ice-covered waters, the design is inefficient for straight forward travel through ice-covered or non-ice-covered waters. The conventional fine hull shape with a long, parallel middle body section is a fuel efficient design. The fuel efficiency of this design is sacrificed to achieve improved maneuverability when the wide beam forward design is utilized.

When the ship is moving straight ahead, the ice is broken by its bow and the unbroken ice tends to hug the sides and develop considerable friction, impeding forward movement. The condition is complicated by the fact that the ice is often "uneven", as a result of channels having been broken and rebroken, with the pieces of ice thrown up into uneven mounds and refreezing in that form. This uneven structure increases the friction and resistance to movement. If straightline movement is difficult, the problem is compounded when the ship tries to turn. In making a turn, under the action of the rudder, the ship pivots about a point about a third of the way from the bow to the stern (this will vary somewhat depending on the design of the vessel and its draft forward as against its draft aft). Bow thrusters are sometimes used to move the bow laterally, but these tend to become fouled in ice and so are not usually employed for winter navigation.

The US Navy has not recently designed surface ships, other than ice breakers, to operate in the Arctic. The problems of ice damage and topside icing when surface ships were operated in high latitudes were handled on an ad hoc basis. From time to time during the design of a new class of surface ships, the issue of ice hardening has arisen. One example was during the design of the Perry (DDG-7) class guided missile frigates. While high latitude operations were envisioned, these ships were heavily cost constrained and the ice hardening characteristic was dropped from consideration during cost tradeoffs.

The Navy and Coast Guard, however, have designed icebreakers, as have commercial interests. Other commercial ships have been designed for ice hardening. Most major classification societies who govern the details of commercial ship hull design have established rules for the design of ship hulls for operations in ice. The American Bureau of Shipping (ABS) would be the relevant classification society for US ship design. ABS Rules require strengthening of the bow and stern areas. Bow mounted sonar domes and arrays in particular would require careful attention. Propellers, rudders, fin stabilizers, and sea chests are also affected by ice operation. The effect of topside icing and a provision to de-ice must also be considered.

Read more!

Pakistan’s Frankenstein Monster

It appears that any time there's an incident like this in India, particularly an incident involving Muslims in India, the government immediately points its finger to Pakistan and often to the area administered by India in Kashmir. How much of this is based on actual evidence and how much just seems to be a reaction that India has to any of these type of incidents?

I think any reporting that you get out of India on these kinds of events that come out within the first few hours is almost certainly not related to some sort of actual data or evidence. It's only through the evidence that they get maybe out of interrogations—this one individual that they actually were able to arrest and presumably interrogate at great length already—that's when you start to realize that they might actually have a sense as to what's really going on. Even then, Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Muhammad are groups that are always named every single time something goes wrong and subsequently we know that they are not always the ones that were directly responsible for the attacks even if they may have some indirect linkages to the groups that actually perpetrated them. So from my perspective, it's always useful to wait at least twenty-four hours and see if some more reliable evidence actually comes out. In this instance, because we're starting to hear about the idea that they came via Karachi, that apparently this one individual they arrested says that he was somehow trained in a Lashkar-e-Taiba camp or was associated with them, it starts to make more sense. But even then, the complexity of these groups, they're not as distinguishable as they once were, or as distinct as they once were. There are multiple and overlapping relationships in terms of the facilities they use and the training and so on.

These two groups have been pegged for years as groups which have at least received support and some training from inside Pakistan to disrupt Indian rule in Kashmir. There are some analysts today that feel the Pakistani government, having developed its own pretty serious terrorist challenge internally, has really lost control of these two groups. Is that fair to say?

I think it's absolutely fair to say that this looks more like a Frankenstein's monster kind of situation in Pakistan than it looks like a directly controlled and manipulated and directed militancy that's driven by the top leadership in Islamabad. So that means exactly what you say, which is that historically these groups Lashkar-e-Taiba, Jaish-e-Muhammad, and others were very clearly in the pay of the Pakistani state intelligence and military. In time, however, what they've done is these groups have developed an independent capacity to raise resources and an independent capacity to plan and prosecute operations in Afghanistan, in India, and, unfortunately for Pakistanis, increasingly within Pakistan. They've turned against the hands that once fed them. So that's the nature of the problem now. It is actually still complicated by the fact that there appears to be evidence of continued complicity or at least passive relations between the Pakistani state and some of these groups.

For years the Israelis tried to hold Yasser Arafat responsible for the actions of various groups that were either within Fatah and described by the Palestinian Authority government as out of control militants or were actually outside it. The Israelis held them responsible one way or another. Is that essentially the Indian position with the Pakistani government here?

I think it had been the Indian position and was certainly the Indian position in 2001-2002, where the Pakistani government and President Pervez Musharraf after the attack on the Indian parliament in December 2001 came out and took some actions, banned some of these organizations, and the Indians still came out and said, "Look, you've got to get your house in order. We blame you; it's your territory." And there are certainly Indians who still believe that. But I think what has changed is that Indians are starting to see evidence that supports the Pakistani claim that their leadership, including their military leadership, is directly threatened by some of these groups. So I think the Indians, at least Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, are somewhat more reluctant to go down that path of just blaming Pakistan because what they see in the Pakistani state is a state of weakness. Now maybe the Israelis saw the same thing in Arafat, and they honestly didn't care. They gave up on him and decided that he could not be, as they say, a partner for peace. And at some point maybe the Indians will come to that conclusion. I'm hopeful that they haven't reached that conclusion yet, that instead what they see in the Pakistani government is a weak but increasingly more well-meaning potential partner.

There's another analysis out there that it's not just these groups which are really out of control of the civilian government in Pakistan, but the ISI, the Intelligence Services, and the military itself really don't appear to be under the complete control of the civilian government. Is that a fair statement?

It's absolutely fair, and I don't think there are too many people who would honestly suggest that the Pakistani civilians completely control their military at all. The military sets it own budget, it sets it operational plans, and although this military head of the army is more amenable to sharing his plans and, in fact to some degree, letting the civilians set a strategic framework for his operations, he's still very much in control of his actual operations and that holds for the ISI as well. So what you have in Pakistan is, in relative terms, a strong and dominant national institution in the army and a relatively weaker civilian political leadership that is only in the very early stages of trying to balance out the influence and sort of come to any kind of command relationship over the military. I think they're a ways off from that.

This crisis in Mumbai occurred as India is building up to national elections. There's a lot of talk about the Congress Party being in some serious trouble now. They're under a lot of pressure and criticism for their handling of the attacks. Should we be wary of public statements from the Indian government right now on this?

You're right, the Congress Party is feeling very much under pressure and I think recognizes that the upcoming national elections weren't looking particularly good for them because of the economic downturn, and this is one more reason why they are probably anticipating a significant loss of support at the polls relative to the last elections. For that reason they're really going to have to—at some level they have to find a face-saving way out of this. The resignation of the home minister is one piece of it. Pressuring the Pakistanis to yield on something will have to be another piece of it, I think. And demonstrating as a government that they are taking firm steps to improve India's internal security will have to be a third piece. All these things are very hard, and I think the opposition BJP, which hasn't been a particularly effective party in opposition, is already looking to exploit this politically.

Up until now, the charges of not providing enough security, which have been leveled by the BJP after a series of attacks in India over the past several years, really haven't stuck. They haven't found an audience. But an event like this, hitting such symbolic targets of Indian wealth and rising power, economic power, is probably going to touch more people and make them more concerned about the state of their national security, possibly shifting some votes toward the BJP, although I have to imagine that the national economy will still be more of a campaign issue in the end.

Now you could look at this in a perspective that says that if there was, in fact, some group that actually crossed the border with Pakistan, India might feel somewhat relieved. It has an enormous Muslim minority and unrest among that group would be maybe an even greater challenge. Is that right?

There is a problem if these kinds of attacks, like some of the ones over recent months apparently have been perpetrated by this group, the Indian Mujahideen, which has at least got some significant indigenous connections, not necessarily from Pakistan or Bangladesh or anywhere else but Indian. And the problem with these indigenous strikes is that they raise questions about India's capacity to actually live and make workable a multi-ethnic, as they say, secular Indian state, to maintain that as a national identity and to make it workable. So if the attack comes from the outside it doesn't necessarily damage that national identity side of things, but it does threaten a cross- border level of violence with their neighbor in Pakistan that is probably almost as dangerous. So different kinds of problems, and yes, in some ways it is nice for the Indian government to be able to point fingers outside the country in terms of a political sense, in a domestic politics sense, but I would say no matter how the Mumbai attack ends up being in terms of who is responsible and where the strings run, they do have an increasing problem with domestic violence or internal violence perpetrated by Indian Muslims and unfortunately it appears Hindu nationalists as well.

What's Washington's role here? It strikes me that this is just an absolute hornet's nest for US policymakers.

It's very difficult, certainly, for the incoming Obama team as they're just getting their footing but also for the Bush administration to do much more than certainly counsel restraint on both sides, and that's clearly happening. The only other piece—because the United States is a country that enjoys relatively good relationships with both governments—is that it can help, if there is a face-saving way to avoid any escalation here, it may be able to help find it and find it rapidly to avoid unnecessary escalation that's driven by politicking on both sides. So that's where a lot of talk—I'm sure the phone lines are burning up; I gather US Secretary [of State Condoleezza] Rice is in Delhi or on her way—that's where the United States can play a role. But it's important to recognize that the India-Pakistan conflict is one that we've seen an improvement in that relationship over the past several years primarily driven by those countries themselves, not by the United States. And there's always been relatively little the United States could do—in the way of leverage that is more significant than what either state has in the way of interests with respect to the other. In other words, the United States can be helpful, and we can help to find solutions. If the two sides are willing and able to put them on the table, it can bring them closer together, but unfortunately it doesn't have the capacity, I think, to impose a solution.

Read more!

Thursday, December 4

Globalization and Clashes of Economic Powers - US and China - Part 1

China held to its hybrid model of a state-directed economic system throughout 2008 as it consolidated its position as one of the world’s fastest-growing countries. Alone among the world’s major economies, China refuses to allow the renminbi (RMB), its currency, to respond to free market movements. China’s leaders instead keep the currency trading at an artificially low level in order to suppress export prices—a deliberate violation of the rules of the International Monetary Fund, of which it is a member. As a result of this and other factors, China’s current account surplus with the United States and the rest of the world soared and added to China’s record foreign exchange reserves of nearly $2 trillion when this Report was completed, up from $1.43 trillion at the publication of the Commission’s Report a year ago. China began employing thisforeign exchange in new ways. Rather than using it to improve the standard of living for the Chinese people through education, health care, or pension systems, China began investing the money through new overseas investment vehicles, including an official sovereign wealth fund, the China Investment Corporation. Despite statements by Chinese leaders that they seek only financial gain from diversifying their investments into equity stakes in western companies,there are increasing suspicions that China intends to use its cash to gain political advantage globally and to lock up supplies of scarce resources around the world. Other Chinese government economic policies harmed the United States, China’s trading partners, and its own citizens. China made scant progress in reining in the rampant counterfeiting and piracy that deprive legitimate foreign businesses operating in China of their intellectual property, while they provide an effective subsidy to Chinese companies that make use of stolen software and other advanced technology. Chinese regulators failed to prevent the domestic sale and export of consumer goods tainted with industrial chemicals and fraudulent ingredients. In one case examined by the Commission, China’s lax controls on the production and handling of its seafood exports led to a partial U.S. ban for health reasons on imported Chinese seafood. Yet, thanks to artificially low prices partly resulting from an array of subsidies to its seafood industry, China has become the largest exporter of seafood to the United States.

The U.S.-China Trade and Economic Relationship’s Current Status and Significant Changes During 2008

* China’s trade surplus with the United States remains large, despite the global economic slowdown. The U.S. trade deficit in goods with China through August 2008 was $167.7 billion, which represents an increase of 2.4 percent over the same period in 2007. Since China joined the WTO in 2001, the United States has accumulated a $1.16 trillion goods deficit with China and, as a result of the persistent trade imbalance, by August 2008 China had accumulated nearly $2 trillion in foreign currency reserves. China’s trade relationship with the United States continues to be severely unbalanced.

* The U.S. current account deficit causes considerable anxiety among both economists and foreign investors who worry that future taxpayers will find it increasingly difficult to meet both principal and interest payments on such a large debt. The total debt burden already is having a significant impact on economic growth, which will only increase in severity.

* China’s currency has strengthened against the U.S. dollar by more than 18.5 percent since the government announced in July 2005 it was transitioning from a hard peg to the dollar to a ‘‘managed float.’’ Starting in July 2008, however, the rate of the RMB’s appreciation has slowed, and there are some indications this may be due to the Chinese government’s fear that a strong RMB will damage China’s exports. China’s RMB remains significantly undervalued.

* China continues to violate its WTO commitments to avoid trade distorting measures. Among the trade-related situations in China that are counter to those commitments are restricted market access for foreign financial news services, books, films and other media; weak intellectual property protection; sustained use of domestic and export subsidies; lack of transparency in regulatory processes; continued emphasis on implementing policies that protect and promote domestic industries to the disadvantage of foreign competition; import barriers and export preferences; and limitations on foreign investment or ownership in certain sectors of the economy.

* Over the past year, China has adopted a battery of new laws and policies that may restrict foreign access to China’s markets and protect and assist domestic producers. These measures include new antimonopoly and patent laws and increased tax rebates to textile manufacturers. The full impact of these laws is not yet known, particularly whether they will help or hinder fair trade and investment.

* In 2008, China emerged as a stronger power within the WTO as it took a more assertive role in the Doha Round of multilateral trade talks, working with India and other less-developed nations to insist on protection for subsistence farmers.

China’s Capital Investment Vehicles and Implications for the U.S. Economy and National Security

* The significant expansion of the Chinese government’s involvement in the international economy in general and in the U.S. economy in particular has concerned many economists and government officials due to uncertainty about the Chinese government’s and the Chinese Communist Party’s motivations, strategies, and possible impacts on market stability and national security. At the same time, cash-strapped U.S. firms have welcomed the investments, viewing them as stable and secure sources of financing in the wake of the credit crunch.

* China’s government uses a number of state-controlled investment vehicles among which it chooses depending on its particular investment purposes and strategies; most widely known among such vehicles are China Investment Corporation (CIC), the State Administration for Foreign Exchange (SAFE), and China International Trust and Investment Corporation (CITIC).

* Some aspects of China Investment Corporation’s mandate follow China’s industrial policy planning and promotion of domestic industries by, for example, investing in natural resources and emerging markets that are relevant for the advancement of China’s value-added industries. CIC and SAFE form just one part of a complex web of state-owned banks, state-owned companies and industries, and pension funds, all of which receive financing and instructions from the central government, promote a state-led development agenda, and have varying levels of transparency. Many of their investment activities contravene official assurances that they are not being managed to wield political influence.

* Regulations governing investments by sovereign wealth funds, especially disclosure requirements pertaining to their transactions and ownership stakes, are still in development, both in the multilateral arena and in the United States. There is concern that the Chinese government can hide its ownership of U.S. companies by using stakes in private equity vehicles like hedge or investment funds.

* China’s foreign exchange reserves continue to grow, while its management of the exchange rate has given it monopoly control on outward flows of investment. This strongly suggests that China will have a very substantial and long-term presence in the U.S. economy through equity stakes; loans; mergers and acquisitions; ownership of land, factories, and companies; and other forms of investment.Research and Development, Technological Advances in Some Key Industries, and Changing Trade Flows with China.

* China has been pursuing a government policy designed to make China a technology superpower and to enhance its exports. Some of its tactics violate free market principles—specifically its use of subsidies and an artificially low RMB value to attract foreign investment. Foreign technology companies, such as U.S. and European computer,aerospace, and automotive firms, have invested heavily in research and development and production facilities in China, sharing or losing technology and other know-how. Chinese manufacturers have benefitted from this investment. The U.S. government has not established any effective policies or mechanisms at the federal level to retain research and development facilities within its borders.

* China’s trade surplus in advanced technology products is growing rapidly, while the United States is running an ever-larger deficit in technology trade. China also is pursuing a strategy of creating an integrated technology sector to reduce its dependence on manufacturing inputs.

* China seeks to become a global power in aerospace and join the United States and Europe in producing large passenger aircraft. China also seeks to join the United States, Germany, and Japan as major global automobile producers. So far as China competes fairly with other nations, this need not be a concern. But China’s penchant for using currency manipulation, industrial subsidies, and intellectual property theft to gain an advantage violates international norms.

China’s Activities Directly Affecting U.S. Security Interests

China’s record of proliferating weapons of mass destruction or effect has improved in recent years, and the nation has played a significant role in some important nonproliferation activities such as the Six-Party Talks intended to denuclearize North Korea. However, the United States continues to have concerns about the commitment of China’s leadership to nonproliferation and to enforcing the strengthened nonproliferation laws and procedures the nation has established and about China’s refusal to participate in some international nonproliferation agreements and regimes. The United States also is concerned that the nuclear power technology China is selling to other nations may result in nuclear proliferation.

China increasingly is devising unique interpretations of agreements or treaties to which it is a party that have the effect of expanding the territory over which it claims sovereignty and rationalizing such expansions, particularly outward from its coast and upward into outer space. This development, coupled with its military modernization, its development of impressive but disturbing

capabilities for military use of space and cyber warfare, and its demonstrated employment of these capabilities, suggest China is intent on expanding its sphere of control even at the expense of its Asian neighbors and the United States and in contravention of international consensus and formal treaties and agreements. These tendencies quite possibly will be exacerbated by China’s growing need for natural resources to support its population and economy that it cannot obtain domestically. The United States should watch these trends closely and act to protect its interests where they are threatened.

China’s Proliferation Policies and Practices

* China has made progress in developing nonproliferation policies and mechanisms to implement those policies. Although it is apparent that China is making some meaningful efforts to establish a culture and norms supporting some aspects of nonproliferation within its bureaucracy and industry, gaps remain in the policies, the strength of government support for them, and their enforcement.

* Although China has acceded to numerous international agreements on nonproliferation and has cooperated with the United States on some nonproliferation issues (e.g., the Six-Party Talks),China has been reluctant to participate fully in U.S.-led nonproliferation efforts such as the Proliferation Security Initiative and in multilateral efforts to persuade Iran to cease its uranium enrichment and other nuclear development activities.

* China’s support for multilateral negotiations with North Korea can help to reduce tensions on the Korean Peninsula, open North Korea to dialogue, and improve bilateral relations among the countries participating in the process—which may be crucial ingredients for peace and cooperation in northeast Asia and beyond.

* Experts have expressed concerns that China’s sales or transfers of nuclear energy technology to other nations may create conditions for proliferation of nuclear weapons expertise, technology, and related materials. These activities also could feed the insecurities of other nations and cause them to pursue their own nuclear weapons development efforts. This could lead to an increase in the number of nations possessing nuclear weapons capability.

China’s Views of Sovereignty and Methods of Controlling Access to its Territory

* China’s leaders adamantly resist any activity they perceive to interfere with China’s claims to territorial sovereignty. At times this priority conflicts with international norms and practices.

* Some experts within China are attempting to assert a view that China is entitled to sovereignty over outer space above its territory, contrary to international practice. If this becomes Chinese policy, it could set the stage for conflict with the United States and other nations that expect the right of passage for their spacecraft.

* China has asserted sovereignty over the seas and airspace in an Exclusive Economic Zone that extends 200 miles from its coastal baseline. This already has produced disputes with the United States and other nations and brings the prospect of conflict in the future.

* Any assertions by Chinese officials of sovereignty in the maritime,air, and outer space domains are not just a bilateral issue between the United States and China. The global economy is dependent upon the fundamental principles of freedom of navigation of the seas and air space, and treatment of outer space as a global ‘‘commons’’ without borders. All nations that benefit from the use of these domains would be adversely affected by the encroachment of Chinese sovereignty claims.

* China’s efforts to alter the balance of sovereignty rights are part of its overall access control strategy and could have an impact on the perceived legitimacy of U.S. military operations in the region, especially in times of crisis.

* China is building a legal case for its own unique interpretation of international treaties and agreements. China is using ‘‘lawfare’’ and other tools of national power to persuade other nations to accept China’s definition of sovereignty in the maritime, air, and space domains.

The Nature and Extent of China’s Space and Cyber Activities and their Implications for U.S. Security

* China continues to make significant progress in developing space capabilities, many of which easily translate to enhanced military capacity. In China, the military runs the space program, and there is no separate, distinguishable civilian program. Although some Chinese space programs have no explicit military intent, many space systems—such as communications, navigation, meteorological, and imagery systems—are dual use in nature.

* The People’s Liberation Army currently has sufficient capability to meet many of its space goals. Planned expansions in electronic and signals intelligence, facilitated in part by new, space-based assets, will provide greatly increased intelligence and targeting capability. These advances will result in an increased threat to U.S. military assets and personnel.

* China’s space architecture contributes to its military’s command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR) capability. This increased capability allows China to project its limited military power in the western and southern Pacific Ocean and to place U.S. forces at risk sooner in any conflict. Cyber space is a critical vulnerability of the U.S. government and economy, since both depend heavily on the use of computers and their connection to the Internet. The dependence on the Internet makes computers and information stored on those computers vulnerable.

* China is likely to take advantage of the U.S. dependence on cyber space for four significant reasons. First, the costs of cyber operations are low in comparison with traditional espionage or military activities. Second, determining the origin of cyber operations and attributing them to the Chinese government or any other operator is difficult. Therefore, the United States would be hindered in responding conventionally to such an attack. Third, cyber attacks can confuse the enemy. Fourth, there is an underdeveloped legal framework to guide responses.

* China is aggressively pursuing cyber warfare capabilities that may provide it with an asymmetric advantage against the United States. In a conflict situation, this advantage would reduce current U.S. conventional military dominance.

Read more!

Monday, December 1

Thinking the unthinkable - The Blood Borders!!!

Here is a controversial article written by Ralph Peters published in Armed Forces Journal. Though the article has been debated extensively on different forums for its political biases and is focused specifically on the Middle East, it helps in thinking about a truly new view of looking at man-made political boundaries of nations which in many cases do not represent the ethnic, cultural and nationalistic identity of the different regions and the people. This underlying cause ranges from Falkland Island in South America to Western Sahara in Morocco; Kurdistan and Baluchistan to Korean peninsula in the east.

This definition of a country or nation can be challenged by many people, but to me this clash of associative identity and superimposed identity is the 'root'- cause of most of the current global conflicts. This question and the ways out, we would explore in the blogs later. I would appreciate if you can drop your thoughts and comments(+-) at the bottom of the blog so that they can help me in formulating and exploring this idea further. The article goes like this :

"Blood borders

How a better Middle East would look

International borders are never completely just. But the degree of injustice they inflict upon those whom frontiers force together or separate makes an enormous difference — often the difference between freedom and oppression, tolerance and atrocity, the rule of law and terrorism, or even peace and war.

The most arbitrary and distorted borders in the world are in Africa and the Middle East. Drawn by self-interested Europeans (who have had sufficient trouble defining their own frontiers), Africa’s borders continue to provoke the deaths of millions of local inhabitants. But the unjust borders in the Middle East — to borrow from Churchill — generate more trouble than can be consumed locally.

While the Middle East has far more problems than dysfunctional borders alone — from cultural stagnation through scandalous inequality to deadly religious extremism — the greatest taboo in striving to understand the region’s comprehensive failure isn’t Islam but the awful-but-sacrosanct international boundaries worshipped by our own diplomats.

Of course, no adjustment of borders, however draconian, could make every minority in the Middle East happy. In some instances, ethnic and religious groups live intermingled and have intermarried. Elsewhere, reunions based on blood or belief might not prove quite as joyous as their current proponents expect. The boundaries projected in the maps accompanying this article redress the wrongs suffered by the most significant “cheated” population groups, such as the Kurds, Baluch and Arab Shia, but still fail to account adequately for Middle Eastern Christians, Bahais, Ismailis, Naqshbandis and many another numerically lesser minorities. And one haunting wrong can never be redressed with a reward of territory: the genocide perpetrated against the Armenians by the dying Ottoman Empire.

Yet, for all the injustices the borders re-imagined here leave unaddressed, without such major boundary revisions, we shall never see a more peaceful Middle East.

Even those who abhor the topic of altering borders would be well-served to engage in an exercise that attempts to conceive a fairer, if still imperfect, amendment of national boundaries between the Bosporus and the Indus. Accepting that international statecraft has never developed effective tools — short of war — for readjusting faulty borders, a mental effort to grasp the Middle East’s “organic” frontiers nonetheless helps us understand the extent of the difficulties we face and will continue to face. We are dealing with colossal, man-made deformities that will not stop generating hatred and violence until they are corrected.

As for those who refuse to “think the unthinkable,” declaring that boundaries must not change and that’s that, it pays to remember that boundaries have never stopped changing through the centuries. Borders have never been static, and many frontiers, from Congo through Kosovo to the Caucasus, are changing even now (as ambassadors and special representatives avert their eyes to study the shine on their wingtips).

Oh, and one other dirty little secret from 5,000 years of history: Ethnic cleansing works.

Begin with the border issue most sensitive to American readers: For Israel to have any hope of living in reasonable peace with its neighbors, it will have to return to its pre-1967 borders — with essential local adjustments for legitimate security concerns. But the issue of the territories surrounding Jerusalem, a city stained with thousands of years of blood, may prove intractable beyond our lifetimes. Where all parties have turned their god into a real-estate tycoon, literal turf battles have a tenacity unrivaled by mere greed for oil wealth or ethnic squabbles. So let us set aside this single overstudied issue and turn to those that are studiously ignored.

The most glaring injustice in the notoriously unjust lands between the Balkan Mountains and the Himalayas is the absence of an independent Kurdish state. There are between 27 million and 36 million Kurds living in contiguous regions in the Middle East (the figures are imprecise because no state has ever allowed an honest census). Greater than the population of present-day Iraq, even the lower figure makes the Kurds the world’s largest ethnic group without a state of its own. Worse, Kurds have been oppressed by every government controlling the hills and mountains where they’ve lived since Xenophon’s day.

The U.S. and its coalition partners missed a glorious chance to begin to correct this injustice after Baghdad’s fall. A Frankenstein’s monster of a state sewn together from ill-fitting parts, Iraq should have been divided into three smaller states immediately. We failed from cowardice and lack of vision, bullying Iraq’s Kurds into supporting the new Iraqi government — which they do wistfully as a quid pro quo for our good will. But were a free plebiscite to be held, make no mistake: Nearly 100 percent of Iraq’s Kurds would vote for independence.

As would the long-suffering Kurds of Turkey, who have endured decades of violent military oppression and a decades-long demotion to “mountain Turks” in an effort to eradicate their identity. While the Kurdish plight at Ankara’s hands has eased somewhat over the past decade, the repression recently intensified again and the eastern fifth of Turkey should be viewed as occupied territory. As for the Kurds of Syria and Iran, they, too, would rush to join an independent Kurdistan if they could. The refusal by the world’s legitimate democracies to champion Kurdish independence is a human-rights sin of omission far worse than the clumsy, minor sins of commission that routinely excite our media. And by the way: A Free Kurdistan, stretching from Diyarbakir through Tabriz, would be the most pro-Western state between Bulgaria and Japan.

A just alignment in the region would leave Iraq’s three Sunni-majority provinces as a truncated state that might eventually choose to unify with a Syria that loses its littoral to a Mediterranean-oriented Greater Lebanon: Phoenecia reborn. The Shia south of old Iraq would form the basis of an Arab Shia State rimming much of the Persian Gulf. Jordan would retain its current territory, with some southward expansion at Saudi expense. For its part, the unnatural state of Saudi Arabia would suffer as great a dismantling as Pakistan.

A root cause of the broad stagnation in the Muslim world is the Saudi royal family’s treatment of Mecca and Medina as their fiefdom. With Islam’s holiest shrines under the police-state control of one of the world’s most bigoted and oppressive regimes — a regime that commands vast, unearned oil wealth — the Saudis have been able to project their Wahhabi vision of a disciplinarian, intolerant faith far beyond their borders. The rise of the Saudis to wealth and, consequently, influence has been the worst thing to happen to the Muslim world as a whole since the time of the Prophet, and the worst thing to happen to Arabs since the Ottoman (if not the Mongol) conquest.

While non-Muslims could not effect a change in the control of Islam’s holy cities, imagine how much healthier the Muslim world might become were Mecca and Medina ruled by a rotating council representative of the world’s major Muslim schools and movements in an Islamic Sacred State — a sort of Muslim super-Vatican — where the future of a great faith might be debated rather than merely decreed. True justice — which we might not like — would also give Saudi Arabia’s coastal oil fields to the Shia Arabs who populate that subregion, while a southeastern quadrant would go to Yemen. Confined to a rump Saudi Homelands Independent Territory around Riyadh, the House of Saud would be capable of far less mischief toward Islam and the world.

Iran, a state with madcap boundaries, would lose a great deal of territory to Unified Azerbaijan, Free Kurdistan, the Arab Shia State and Free Baluchistan, but would gain the provinces around Herat in today’s Afghanistan — a region with a historical and linguistic affinity for Persia. Iran would, in effect, become an ethnic Persian state again, with the most difficult question being whether or not it should keep the port of Bandar Abbas or surrender it to the Arab Shia State.

What Afghanistan would lose to Persia in the west, it would gain in the east, as Pakistan’s Northwest Frontier tribes would be reunited with their Afghan brethren (the point of this exercise is not to draw maps as we would like them but as local populations would prefer them). Pakistan, another unnatural state, would also lose its Baluch territory to Free Baluchistan. The remaining “natural” Pakistan would lie entirely east of the Indus, except for a westward spur near Karachi.

The city-states of the United Arab Emirates would have a mixed fate — as they probably will in reality. Some might be incorporated in the Arab Shia State ringing much of the Persian Gulf (a state more likely to evolve as a counterbalance to, rather than an ally of, Persian Iran). Since all puritanical cultures are hypocritical, Dubai, of necessity, would be allowed to retain its playground status for rich debauchees. Kuwait would remain within its current borders, as would Oman.

In each case, this hypothetical redrawing of boundaries reflects ethnic affinities and religious communalism — in some cases, both. Of course, if we could wave a magic wand and amend the borders under discussion, we would certainly prefer to do so selectively. Yet, studying the revised map, in contrast to the map illustrating today’s boundaries, offers some sense of the great wrongs borders drawn by Frenchmen and Englishmen in the 20th century did to a region struggling to emerge from the humiliations and defeats of the 19th century.

Correcting borders to reflect the will of the people may be impossible. For now. But given time — and the inevitable attendant bloodshed — new and natural borders will emerge. Babylon has fallen more than once.

Meanwhile, our men and women in uniform will continue to fight for security from terrorism, for the prospect of democracy and for access to oil supplies in a region that is destined to fight itself. The current human divisions and forced unions between Ankara and Karachi, taken together with the region’s self-inflicted woes, form as perfect a breeding ground for religious extremism, a culture of blame and the recruitment of terrorists as anyone could design. Where men and women look ruefully at their borders, they look enthusiastically for enemies.

From the world’s oversupply of terrorists to its paucity of energy supplies, the current deformations of the Middle East promise a worsening, not an improving, situation. In a region where only the worst aspects of nationalism ever took hold and where the most debased aspects of religion threaten to dominate a disappointed faith, the U.S., its allies and, above all, our armed forces can look for crises without end. While Iraq may provide a counterexample of hope — if we do not quit its soil prematurely — the rest of this vast region offers worsening problems on almost every front.

If the borders of the greater Middle East cannot be amended to reflect the natural ties of blood and faith, we may take it as an article of faith that a portion of the bloodshed in the region will continue to be our own."

Read more!

Militant Attacks In Mumbai and Their Consequences

On 26/11, a group of Islamist operatives carried out a complex terror operation in the Indian city of Mumbai. The attack was not complex because of the weapons used or its size, but in the apparent training, multiple methods of approaching the city and excellent operational security and discipline in the final phases of the operation, when the last remaining attackers held out in the Taj Mahal hotel for several days. The operational goal of the attack clearly was to cause as many casualties as possible, particularly among Jews and well-to-do guests of five-star hotels. But attacks on various other targets, from railroad stations to hospitals, indicate that the more general purpose was to spread terror in a major Indian city.

While it is not clear precisely who carried out the Mumbai attack, two separate units apparently were involved. One group, possibly consisting of Indian Muslims, was established in Mumbai ahead of the attacks. The second group appears to have just arrived. It traveled via ship from Karachi, Pakistan, later hijacked a small Indian vessel to get past Indian coastal patrols, and ultimately landed near Mumbai.

Extensive preparations apparently had been made, including surveillance of the targets. So while the precise number of attackers remains unclear, the attack clearly was well-planned and well-executed.

Evidence and logic suggest that radical Pakistani Islamists carried out the attack. These groups have a highly complex and deliberately amorphous structure. Rather than being centrally controlled, ad hoc teams are created with links to one or more groups. Conceivably, they might have lacked links to any group, but this is hard to believe. Too much planning and training were involved in this attack for it to have been conceived by a bunch of guys in a garage. While precisely which radical Pakistani Islamist group or groups were involved is unknown, the Mumbai attack appears to have originated in Pakistan. It could have been linked to al Qaeda prime or its various franchises and/or to Kashmiri insurgents.

More important than the question of the exact group that carried out the attack, however, is the attackers’ strategic end. There is a tendency to regard terror attacks as ends in themselves, carried out simply for the sake of spreading terror. In the highly politicized atmosphere of Pakistan’s radical Islamist factions, however, terror frequently has a more sophisticated and strategic purpose. Whoever invested the time and took the risk in organizing this attack had a reason to do so. Let’s work backward to that reason by examining the logical outcomes following this attack.

An End to New Delhi's Restraint

The most striking aspect of the Mumbai attack is the challenge it presents to the Indian government — a challenge almost impossible for New Delhi to ignore. A December 2001 Islamist attack on the Indian parliament triggered an intense confrontation between India and Pakistan. Since then, New Delhi has not responded in a dramatic fashion to numerous Islamist attacks against India that were traceable to Pakistan. The Mumbai attack, by contrast, aimed to force a response from New Delhi by being so grievous that any Indian government showing only a muted reaction to it would fall.

India’s restrained response to Islamist attacks (even those originating in Pakistan) in recent years has come about because New Delhi has understood that, for a host of reasons, Islamabad has been unable to control radical Pakistani Islamist groups. India did not want war with Pakistan; it felt it had more important issues to deal with. New Delhi therefore accepted Islamabad’s assurances that Pakistan would do its best to curb terror attacks, and after suitable posturing, allowed tensions originating from Islamist attacks to pass.